What leader has not been taught the anecdote to understanding and solving a problem? Asking “why” five times is the simplest way to get to the root cause of an issue. In the last two decades, the United States has been crippled by three devastating problems that just don’t seem to be getting any better. When I ask “why” five times, I get the same root cause answer for all three problems.

The first problem is the constant rise of chronic conditions in the United States. In 2012, half of all adults — 117 million people — had one or more chronic health conditions.1 Statistics state 141 million people were living with a chronic condition in 2010. It is expected to be 171 million by 2030.2 Despite the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the focus on population health, the prevalence of disease management, and the steady rise of available wellness programs and resources, why is the number of people with a chronic condition still rapidly increasing?

It’s because we have not dug deep enough to figure out and address the root cause of the problem. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the root cause of this chronic disease epidemic is a lack of physical activity and poor nutrition, which alone or in combination contribute to obesity and its attendant consequences.3 I beg the WHO to ask “why” a couple more times. “Why is there a lack of physical activity and poor nutrition leading to obesity?” That answer brings us a little closer to the root cause of the problem.

Unlike medical issues that can be diagnosed with blood tests or broken bones that can be identified with an X-ray, there is no one-size-fits-all prescription for a mental health issue.

The second problem is the newly declared opioid epidemic. The rate of overdose deaths involving opioids has risen 280 percent between 2002 and 2015, and it’s continuing to climb.4

The third problem is the steady climb in mass shootings during the last 20 years, with a major spike in the last decade. On average there were 6.4 shootings per year from 2000 to 2006. From 2007 to 2013 there were 16.4 shootings a year.5 In 2017, CNN reported an average of almost 7 mass shootings per week. There were a total of 307 shootings between January 1, 2017 and November 5, 2017.6

With all three issues, there are arguable points that I would agree fuel these problems. Yes, many chronic conditions are genetic. Yes, opioids are overprescribed. It is relatively easy, even for those with mental health problems, to obtain the weapons used in individual and mass killings. However, these aren’t the root causes of the problems, and, although we need to band together and commit to initiatives that support positive change, the problems won’t be permanently solved until the real root cause is realized and addressed.

How Mental Health Fits In

About the fourth time you ask “why” to each of these three problems, the answer you get is “untreated mental or emotional health issues.” I am not talking about only the one in 17 Americans who lives with a diagnosed serious mental illness such as schizophrenia, major depression or bipolar disorder. I am also speaking about the one in four American adults who experiences a mental health problem each and every year. These mental or emotional issues are most often undiagnosed and can happen to anyone at any age, with any level of education and from any culture, race, religion or socioeconomic background. They can be initiated simply by a sudden turn of events or an unexpected situation such as physical trauma; the loss of a loved one; the end of a relationship; a difficult medical diagnosis of a child, spouse or parent; or the loss of a job or income. If the feelings associated with these issues—such as stress, grief, anger, fear, sadness, moodiness, low self-esteem and loneliness—are not adequately addressed and resolved, and if healthy coping skills are not adopted, these mental health issues will be exacerbated and evolve into more chronic and dangerous threats to the health and safety of the individual, and potentially others. Over time, especially as additional life challenges are faced, it becomes increasingly more difficult to unwind and reverse the effects of ignoring these old demons.

Back to the three main problems. If there is any doubt that mental health is close to the core of these problems, let’s consider the following facts:

- Mental illness is associated with an increased occurrence of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, asthma, epilepsy and cancer.7

- Mental illness is associated with lower use of medical care, reduced adherence to treatment therapies for chronic diseases and higher risks of adverse health outcomes.8

- According to the CDC, 43 percent of people with depression are obese, compared with a third of the general population.9 One 2010 study found that people who are obese are 55 percent more likely to be depressed, and people with depression are 58 percent more likely to develop obesity.10

- A study published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine found that adults with a mental illness received more than 50 percent of the annual 115 million opioid prescriptions in the United States. The study found that nearly 19 percent of Americans with mental health issues use prescription opioids, while the same is true for only 5 percent of those without a mental health condition.11

- At least 59 percent of the 185 public mass shootings that took place in the United States from 1900 through 2017 were carried out by people who had either been diagnosed with a mental disorder or demonstrated signs of serious mental illness prior to the attack.12 Mother Jones found a similarly high rate of potential mental health problems among perpetrators of mass shootings—61 percent—when the magazine examined 62 cases in 2012.13 Both rates are considerably higher than those found in the general population.14

Although mental health disorders require ongoing treatment, early diagnosis and intervention can decrease the burden of these conditions, associated with chronic diseases and other risks. There is so much written about the progress that has been made in the last two decades in treating and preventing mental illness. Yet this leads us to the fifth “why” and the crux of our three problems: why are there still so many people with untreated mental health disorders?

Addressing the Lack of Care

I recognize the stigma and fear associated with asking for help. However, I believe there are plenty of people who are ready to get help for themselves or a loved one and can’t. Many say there is a shortage of mental health providers in the United States. Insurance networks claim they have plenty of providers and their panels are full, so they are not accepting new providers. I submit that there likely is a shortage of quality mental health providers who will accept insurance.

Day in and day out my company assists individuals in connecting with qualified mental health treatment providers and resources, so I can attest that this is no easy feat, especially when left to an individual in distress. I recently read an article titled “Single Mom’s Search for Therapist Foiled by Insurance Companies” that supported the frustration my team faces daily. It explained a study the authors conducted in which they attempted to get an evening appointment with an in-network mental health provider in or near a large city in California. They called 100 providers from an insurance company’s provider directory; they could find only 28 who were accepting new patients and would take the insurance. Of those, only eight had an appointment time available after regular working hours.15

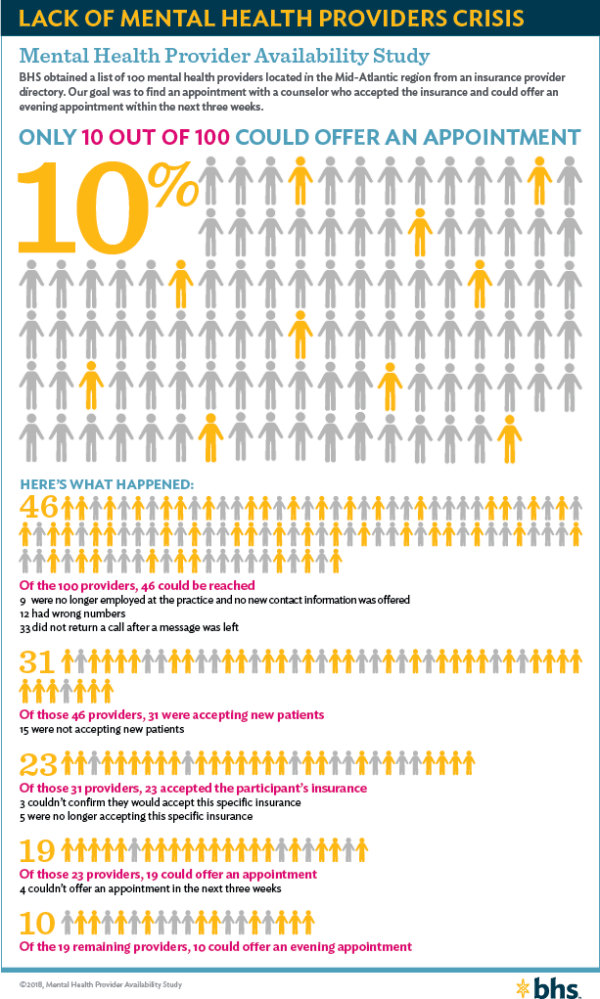

My team decided to repeat the study on the other side of the country, using a different insurance company directory. We contacted 100 providers in the Mid-Atlantic region. Twelve providers had incorrect phone numbers listed in the provider directory; nine were no longer employed at the practice and no new contact information was offered; and 33 did not answer or return a call after a message was left. Of the 46 providers we reached, 15 were not accepting new patients. Of the 31 providers who were accepting new patients, five no longer accepted the specific insurance we were using, and three couldn’t confirm that they would accept it. Of the remaining 23 providers, four couldn’t offer any appointments within the next three weeks; of the last 19, only 10 could offer an evening appointment.

There are many reasons why mental health providers no longer accept insurance. The primary reason is likely because reimbursement rates provided by insurance companies are not deemed to be at an acceptable level by providers. In spite of the rising costs of all other forms of health care, mental health providers haven’t seen meaningful increases in decades. The reimbursement rate from an insurance company is less than half of what a provider could receive from a private pay client. In addition, health insurance companies require a great deal of paperwork before they release payment. For every hour of counseling, it takes an additional half-hour to complete and file paperwork, not to mention the time for following up, to receive payment. On top of that, there is no guarantee the provider will get paid. Unlike medical issues that can be diagnosed with blood tests or broken bones that can be identified with an X-ray, there is no one-size-fits-all prescription for a mental health issue. Each person needs something different, and what that person needs may or may not be authorized for payment by the insurance company. Finally, many issues for which an individual may seek assistance to prevent a problem from escalating into a mental health disorder are not covered by insurance. The rise of the high-deductible plan has not helped. Clients often don’t understand their benefits; they show up for a counseling appointment without having met their deductible, and once they realize they can’t afford the deductible, they decide they’ll just live with their mental health issue, which seems easier than living with a broken bone. As a result, some clients might not fully pay their therapists, which may influence these providers’ decision to stop participating in insurance networks.

When we figure out how to remove the burden associated with accepting insurance and to better reimburse mental health providers—while holding them accountable for producing quality client outcomes—we will begin to make progress in combating chronic disease, the opioid epidemic and mass violence. Until then, in my opinion, we will only continue discussing excuses.

ENDNOTES

1 Ward, Brian W., Jeannine S. Schiller and Richard A. Goodman. 2014. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: A 2012 update. Preventing Chronic Disease 11: E62.

2 Mattke, Soeren, Tewodaj Mengistu, Lisa Klautzer, Elizabeth M. Sloss, and Robert H. Brook. 2015. Improving Care for Chronic Conditions: Current Practices and Future Trends in Health Plan Programs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR300/RR393/RAND_RR393 .pdf (accessed April 6, 2018).

3 Fryar, Cheryl D., Margaret D. Carroll, and Cynthia L. Ogden. 2012. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Extreme Obesity Among Adults: United States, Trends 1960–1962 Through 2009–2010 [data brief]. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_09_10/ obesity_adult_09_10.pdf

4 Overdose Death Rates. 2017. National Institute on Drug Abuse. September. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death -rates (accessed April 6, 2018).

5 Schmidt, Michael S. FBI Confirms a Sharp Rise in Mass Shootings Since 2000. New York Times, Sept. 24, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/25/us/25shooters .html.

6 Willingham, A.J., and Saeed Ahmed. Mass Shootings in America are a Serious Problem—and These 9 Charts Show Just Why. CNN, November 6, 2017, https:// www.cnn.com/2016/06/13/health/mass-shootings-in-america-in-charts-and -graphs-trnd/index.html (accessed April 6, 2018).

7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Report: Mental Illness Surveillance Among Adults in the United States, CDC Mental Illness Surveillance, December 2, 2011, https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealthsurveillance/fact_sheet .html (accessed March 28, 2018).

8 Ibid.

9 Pratt, Laura A., and Debra J. Brody. Depression and Obesity in the U.S. Adult Household Population, 2005–2010 [data brief], National Center for Health Statistics, October 2014, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db167.htm (accessed March 28, 2018).

10 Luppino, Floriana S., Leonore M. de Wit, and Paul F. Bouvy. 2010. Overweight, Obesity, and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Archives of General Psychiatry 67, 3: 220–229. Available at https:// jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/210608 (accessed March 28, 2018).

11 Davis, Matthew A., Lewei A. Lin, Haiyin Liu, and Brian D. Sites. 2017. Prescription Opiod Use Among Adults With Mental Health Disorders in the United States. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 30, 4: 1–11. Available at https:// kaiserhealthnews.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/opioidembargo-article.pdf (accessed March 28, 2018).

12 Duwe, Grant, and Michael Rocque. Actually, There is a Clear Link Between Mass Shootings and Mental Illness. LA Times, Feb. 23, 2018. http://www.latimes .com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-duwe-rocque-mass-shootings-mental-illness-20180223 -story.html.

13 Follman, Mark. Mass Shootings: Maybe What We Need is a Better Mental-health Policy. Mother Jones, Nov. 9, 2012. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012 /11/jared-loughner-mass-shootings-mental-illness/.

14 Duwe, Grant, and Michael Rocque. Actually, there is a clear link between mental illness and mass shootings. LA Times, February 23, 2018, http://www.latimes .com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-duwe-rocque-mass-shootings-mental-illness-20180223 -story.html (accessed March 28, 2018).

15 Dembosky, April. Single Mom’s Search for Therapist Foiled by Insurance Companies. KQED, July 15, 2016, https://www.kqed.org/stateofhealth/185796/single -moms-search-for-therapist-foiled-by-insurance-companies (accessed April 6, 2018).

_______________

This article originally appeared in the Society of Actuaries newsletter Health Watch, Issue 86 – June 2018